It's Friday morning and, as usual, I'm at the FINRA website looking at recent disciplinary actions. For the month of October there are about 40 pages' worth of infractions, ranging from recordkeeping mishaps to outright bad behavior. I'll place the link below, or you can just go to http://www.finra.org/, then "industry professionals," and then look under "enforcement" for "disciplinary actions." This month you'll find several small fines resulting from sloppy reporting of trades. You'll notice that the same firm often has two or three violations in the same month. And you'll see that Regulation SHO, in which short sales have to be executed very carefully and properly, is a hot topic for the regulators. Reg SHO is all about making sure that when shares are sold short, there actually are shares available. Otherwise, the laws of supply and demand are being manipulated, and market manipulation is the number-one thing that the SEC and FINRA try to prevent. Before executing the short sale, the broker-dealer has to locate the securities and reasonably believe they can be delivered. Of course, the procedures involved to "locate" the securities are new, and it's tough to get the supervisory system in place. Luckily, FINRA is there to help motivate the firms to improve their systems by handing out fines and naming names .

I'll let you take it from here:

http://www.finra.org/web/groups/industry/@ip/@enf/@da/documents/disciplinaryactions/p120231.pdf

Friday, October 30, 2009

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Taxation on OID municipal bonds

A Series 7 customer just emailed me to question the tax treatment for original issue discount (OID) municipal bonds. To be honest, I've never felt 100% comfortable teaching on this topic and should have done some research on it a long time ago. So, no matter how dry an email about the veracity of taxation on original issue discount municipal securities might seem, I was actually quite pumped to dive in. Luckily, I've been doing so much searching at http://www.irs.gov/ lately that I was able to find what I needed in less than one minute. And, luckily, all I needed was Publication 550. That, plus a handful of Excedrin, the reading skills of an attorney, and the patience of Job. But, in the end I was rewarded by knowing that the way I teach taxation on discounted municipal bonds is, apparently, exactly right. I also noticed that I do, apparently, provide a useful service for Series 7 candidates by taking nearly incomprehensible English and making sense of it. In my Pass the 7 book, I try to keep it simple. In the book, my job is to tell you that an original issue discount (OID) municipal bond is treated differently from a STRIP. Since the interest on a STRIP is taxable, you have to report some interest income you haven't actually received on 1099-OID each year and pay tax on it. But, a muni is tax-exempt; therefore, you don't have to pay tax on anything and don't have to file anything. If you sell the bond before maturity, you get to step up your cost-basis to help reduce or eliminate a capital gain on the bond. I also then point out that when you buy a tax-exempt (muni) bond at a discount from an investor, things are wholly different. Now, that discount is taxable . . . as ordinary income!

Turns out, that is exactly right, no matter how strange it seems. But what really struck me is how difficult it is to get that all from the orginal bureaucratic, legalistic version. This is how the IRS explains what I just wrote above (From Publication 550) :

Original issue discount. Original issue discount (OID) on tax-exempt state or local government bonds is treated as tax-exempt interest. If the bonds were issued after September 3, 1982, and acquired after March 1, 1984, increase the adjusted basis by your part of the OID to figure gain or loss.

Discounted tax-exempt obligations. OID on tax-exempt obligations is generally not taxable. However, when you dispose of a tax-exempt obligation you must accrue OID on the obligation to determine its adjusted basis. The accrued OID is added to the basis of the obligation to determine your gain or loss.

Market discount. Market discount on a tax-exempt bond is not tax-exempt. If you bought the bond after April 30, 1993, you can choose to accrue the market discount over the period you own the bond and include it in your income currently, as taxable interest. If you do not make that choice, or if you bought the bond before May 1, 1993, any gain from market discount is taxable.

I guess what also struck me was how much I enjoyed reading Publication 550 and how much I, apparently, need to find myself a hobby.

Turns out, that is exactly right, no matter how strange it seems. But what really struck me is how difficult it is to get that all from the orginal bureaucratic, legalistic version. This is how the IRS explains what I just wrote above (From Publication 550) :

Original issue discount. Original issue discount (OID) on tax-exempt state or local government bonds is treated as tax-exempt interest. If the bonds were issued after September 3, 1982, and acquired after March 1, 1984, increase the adjusted basis by your part of the OID to figure gain or loss.

Discounted tax-exempt obligations. OID on tax-exempt obligations is generally not taxable. However, when you dispose of a tax-exempt obligation you must accrue OID on the obligation to determine its adjusted basis. The accrued OID is added to the basis of the obligation to determine your gain or loss.

Market discount. Market discount on a tax-exempt bond is not tax-exempt. If you bought the bond after April 30, 1993, you can choose to accrue the market discount over the period you own the bond and include it in your income currently, as taxable interest. If you do not make that choice, or if you bought the bond before May 1, 1993, any gain from market discount is taxable.

I guess what also struck me was how much I enjoyed reading Publication 550 and how much I, apparently, need to find myself a hobby.

Friday, October 23, 2009

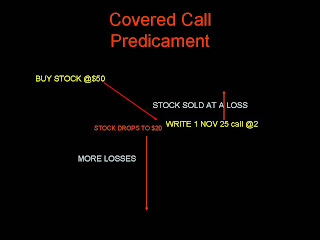

Why I Hate Covered Calls

During the Friday Free Broadcast this morning I showed the attendees one of my account statements. One of the gentlemen in attendance saw a couple of steep losses and suggested that I write some covered calls to "get my money back on those stocks." At first glance, maybe it seems that collecting premiums $2 or $3 per-share at a time might help me recoup some losses on the stock. But the closer you look at covered calls, the less you find to like. In one sense, it isn't even possible to do what he suggests. Why not? If you bought the stock for $50 a share, and it's now worth $20 a share, there will be no strike prices at 50 or above even offered by the options exchange . . . or, if they are available you would get so little premium income writing these frightfully deep-out-of-the-money calls that it wouldn't be worth doing. If the stock is at $20, nobody wants to bet you it's going above $50 any time soon. To collect any decent premium on a $20 stock, the strike price has to be near $20. So, let's see if we have this right--we pay $50 a share for the stock. Now in order to collect $2 or $3 per share in call premiums, we have to be willing to sell the stock for $20 or $25? This is how I get my money back?

Not a chance. The only way to make money on a covered call is to have the stock price remain near your purchase price--and, gee, isn't that sort of what all stock investors would like? If you buy the stock at $50 and sell a Nov 55 call @2, you're okay as long as the stock stays at $48 or higher, but never goes above $55. If the stock drops below $48, you lose just like any other owner of that stock. But--and here is why I absolutely hate covered calls--unlike any other owner of that stock, should the stock go way up, you make none of the upside above $55. None of it. So, you're still exposed to the downside by nearly as much as any other owner--it's just the premium that separates you--but you also sold away your upside for $2 a share, capping it at $7 per share, no matter how high the stock goes.

Of course, it's not likely that a stock will drop to zero that fast, but if the $50 stock drops $10, $20, maybe $30 per share, your days of writing covered calls on it are over. As I mentioned, the strike prices can't be $20 or $30 below your purchase price if you want to make a profit. Right? Could you place a sell-stop below the purchase price? Not really--if that stock is sold automatically, the call you wrote is suddenly naked.

Anyway, next time you hear somebody on the radio or the Internet trying to convince you that covered calls = investment nirvana, factor in some of what I just wrote. And, if you can follow what I just wrote, that's a good sign that you can understand even the toughest options questions.

Not a chance. The only way to make money on a covered call is to have the stock price remain near your purchase price--and, gee, isn't that sort of what all stock investors would like? If you buy the stock at $50 and sell a Nov 55 call @2, you're okay as long as the stock stays at $48 or higher, but never goes above $55. If the stock drops below $48, you lose just like any other owner of that stock. But--and here is why I absolutely hate covered calls--unlike any other owner of that stock, should the stock go way up, you make none of the upside above $55. None of it. So, you're still exposed to the downside by nearly as much as any other owner--it's just the premium that separates you--but you also sold away your upside for $2 a share, capping it at $7 per share, no matter how high the stock goes.

Of course, it's not likely that a stock will drop to zero that fast, but if the $50 stock drops $10, $20, maybe $30 per share, your days of writing covered calls on it are over. As I mentioned, the strike prices can't be $20 or $30 below your purchase price if you want to make a profit. Right? Could you place a sell-stop below the purchase price? Not really--if that stock is sold automatically, the call you wrote is suddenly naked.

Anyway, next time you hear somebody on the radio or the Internet trying to convince you that covered calls = investment nirvana, factor in some of what I just wrote. And, if you can follow what I just wrote, that's a good sign that you can understand even the toughest options questions.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Municipal Securities Question

When studying for the Series 7, it would be nearly impossible to work "too many" municipal securities practice questions. Remember that you will see at least as many questions on municipal securities as you see on options. And, options are much easier to work with--once you understand how they work, it makes no difference how they ask the question. With municipal securities questions, you're often struggling to recall an arcane vocabulary word, or the question is extremely vague. How would you answer the following question on municipal securities?

Which of the following represent(s) an accurate statement?

A. Municipal bonds are traded on a highly liquid secondary market

B. Some municipal bonds pay interest that is non-tax-exempt at the federal level

C. Municipal bonds are exempt from registration requirements

D. All choices listed

First, municipal securities are not highly liquid; in fact, many are illiquid. The school district in which I live recently raised $2,000,000 by selling municipal securities. That means if the bonds were par value of $1,000, there were only 2,000 bonds issued. If the bonds were $5,000 par value, there are only 400 bonds in the entire issue. There is no way that thing could have a liquid secondary market. Secondly, most but not all municipal bonds pay tax-exempt interest. I have an official statement from the City of New York here on my desk. One issue is for $9.2 billion and is described as tax-exempt by the bond counsel. The other issue is for a mere $80 million and is not tax-exempt. Perhaps if I were more curious about the Internal Revenue Code I would track down why the second issue is not tax-exempt, but I'm not, so I won't. But I can now eliminate Choice A and Choice B and, therefore, Choice D has to go, as well.

Leaving me with my answer: C

Which of the following represent(s) an accurate statement?

A. Municipal bonds are traded on a highly liquid secondary market

B. Some municipal bonds pay interest that is non-tax-exempt at the federal level

C. Municipal bonds are exempt from registration requirements

D. All choices listed

First, municipal securities are not highly liquid; in fact, many are illiquid. The school district in which I live recently raised $2,000,000 by selling municipal securities. That means if the bonds were par value of $1,000, there were only 2,000 bonds issued. If the bonds were $5,000 par value, there are only 400 bonds in the entire issue. There is no way that thing could have a liquid secondary market. Secondly, most but not all municipal bonds pay tax-exempt interest. I have an official statement from the City of New York here on my desk. One issue is for $9.2 billion and is described as tax-exempt by the bond counsel. The other issue is for a mere $80 million and is not tax-exempt. Perhaps if I were more curious about the Internal Revenue Code I would track down why the second issue is not tax-exempt, but I'm not, so I won't. But I can now eliminate Choice A and Choice B and, therefore, Choice D has to go, as well.

Leaving me with my answer: C

Monday, October 12, 2009

What's the best way to prepare for the Series 7?

I hear the following question all the time: what's the best way to study for my test?

The answer?

Hard. Really hard.

Seriously. This exam is not just trying to flunk you--it's trying to harass and humiliate you. On any given day, 2/3 of all test-takers fail the Series 7 exam. Obviously, FINRA likes it that way. And, why wouldn't they? The more times people have to take and re-take the exam, the more testing fees they generate.

Okay, so it's a hard test. You already knew that--the question is, what's the best way to study for it?

I recommend that you study 5 days a week for a total of about 20 hours, and that you do this for about 8 weeks in a row. At a minimum.

Seriously.

So, after you buy the Pass the 7 full package plus DVD (http://www.passthe7.com/), I recommend that you watch the DVD lesson that corresponds to each Pass the 7 book chapter first. Then, I would read the book chapter. Then, I would watch the DVD lesson again. Then, I would do all the practice questions on that chapter. And, yes, that would take me a lot of time, but I would really know something about that chapter before I moved on to the next one. Also, it's very easy to pop in a DVD and hit the Play button--after a few minutes of that, you'll be awake enough to put in an hour or so of hard, concentrated reading. Watching the DVD lesson once again will be a nice cool-down after reading, and then applying what you've studied to the practice questions will kick it all up a notch and leave you with that satisfied post-study buzz that will allow you to get some sleep. Face it, you have to sleep the two or three months that you study for your Series 7. And eat. And live your life like a normal person. If you go into the testing center looking and feeling like a zombie, you have statistically no chance of passing.

Once you've gotten through the book and done all the questions by-topic, it's time to take some final exams, which you'll probably do for the last week or two before your exam. Make sure you aren't memorizing answers, because whatever you study will not look exactly like the exam, no matter how hard the company markets their "expertise," or "results." We have some "Go No Go" exams that we can send a link to, so send an email. We'll also talk more about studying for the exam, trying to keep it as concise as possible.

The answer?

Hard. Really hard.

Seriously. This exam is not just trying to flunk you--it's trying to harass and humiliate you. On any given day, 2/3 of all test-takers fail the Series 7 exam. Obviously, FINRA likes it that way. And, why wouldn't they? The more times people have to take and re-take the exam, the more testing fees they generate.

Okay, so it's a hard test. You already knew that--the question is, what's the best way to study for it?

I recommend that you study 5 days a week for a total of about 20 hours, and that you do this for about 8 weeks in a row. At a minimum.

Seriously.

So, after you buy the Pass the 7 full package plus DVD (http://www.passthe7.com/), I recommend that you watch the DVD lesson that corresponds to each Pass the 7 book chapter first. Then, I would read the book chapter. Then, I would watch the DVD lesson again. Then, I would do all the practice questions on that chapter. And, yes, that would take me a lot of time, but I would really know something about that chapter before I moved on to the next one. Also, it's very easy to pop in a DVD and hit the Play button--after a few minutes of that, you'll be awake enough to put in an hour or so of hard, concentrated reading. Watching the DVD lesson once again will be a nice cool-down after reading, and then applying what you've studied to the practice questions will kick it all up a notch and leave you with that satisfied post-study buzz that will allow you to get some sleep. Face it, you have to sleep the two or three months that you study for your Series 7. And eat. And live your life like a normal person. If you go into the testing center looking and feeling like a zombie, you have statistically no chance of passing.

Once you've gotten through the book and done all the questions by-topic, it's time to take some final exams, which you'll probably do for the last week or two before your exam. Make sure you aren't memorizing answers, because whatever you study will not look exactly like the exam, no matter how hard the company markets their "expertise," or "results." We have some "Go No Go" exams that we can send a link to, so send an email. We'll also talk more about studying for the exam, trying to keep it as concise as possible.

Sunday, October 11, 2009

Annuity Payout

I just uploaded seven Series 7 recorded classes that you can purchase "on demand" at www.passthe7.com/classes.htm. There are three lessons on options, two that break down 20 practice questions step by step, one on trading securities, and one on retirement and annuities. The following practice question is on variable annuities and is exactly the sort of thing that pops up on the Series 7 exam.

So, please enjoy:

An annuitant chooses life with a 10-year period certain. If the annuitant lives 12 years, what happens?

A. the beneficiary receives two years of payments

B. the annuity pays out for just 10 years

C. the annuity pays out for 12 years

D. annuity units are converted back to accumulation units

EXPLANTION: with a 10-year "period certain" the annuity company will pay for at least 10 years but will also pay as long as the annuitant lives. Whichever turns out to be longer--that's how long they end up paying, either to the annuitant or the beneficiary after the annuitant dies.

ANSWER: C

So, please enjoy:

An annuitant chooses life with a 10-year period certain. If the annuitant lives 12 years, what happens?

A. the beneficiary receives two years of payments

B. the annuity pays out for just 10 years

C. the annuity pays out for 12 years

D. annuity units are converted back to accumulation units

EXPLANTION: with a 10-year "period certain" the annuity company will pay for at least 10 years but will also pay as long as the annuitant lives. Whichever turns out to be longer--that's how long they end up paying, either to the annuitant or the beneficiary after the annuitant dies.

ANSWER: C

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

IRA Contributions

Let's look at a practice question on IRA contributions.

Which of the following could reduce the amount that an individual may contribute to a Traditional IRA?

A. Roth IRA contributions made for the year

B. High income level

C. Participation in an employer-sponsored plan

D. All of the choices listed

EXPLANATION: if you were going too fast, you might have been tricked by this one. The other choices only affect how much can be deducted from the contribution, but anyone with earned income can contribute to their Traditional IRA.

ANSWER: A

Which of the following could reduce the amount that an individual may contribute to a Traditional IRA?

A. Roth IRA contributions made for the year

B. High income level

C. Participation in an employer-sponsored plan

D. All of the choices listed

EXPLANATION: if you were going too fast, you might have been tricked by this one. The other choices only affect how much can be deducted from the contribution, but anyone with earned income can contribute to their Traditional IRA.

ANSWER: A

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Margin Question on Combined Equity

Let's enjoy a fun question on margin accounts:

One of your investors has both long and short stock positions in her margin account. Today, if the value of the long positions increases by $4,000 and the value of her short positions increases by $2,000, the combined equity will

A. increase by $6,000

B. increase by $2,000

C. decrease by $2,000

D. decrease by $6,000

EXPLANATION: remember that you want the value of a short position to drop. It’s nice that the long position advanced $4,000, but that was reduced by the $2,000 advance in the short position’s value

ANSWER: B

One of your investors has both long and short stock positions in her margin account. Today, if the value of the long positions increases by $4,000 and the value of her short positions increases by $2,000, the combined equity will

A. increase by $6,000

B. increase by $2,000

C. decrease by $2,000

D. decrease by $6,000

EXPLANATION: remember that you want the value of a short position to drop. It’s nice that the long position advanced $4,000, but that was reduced by the $2,000 advance in the short position’s value

ANSWER: B

Saturday, October 3, 2009

Covered Call question

A customer just emailed me with the following concern:

I saw a question like the one below on the software my firm gave me--I think it's an internal product somebody higher up put together. I don't think there's a right answer. Can you help?

Here is the qestion:

An investor purchases 300 shares ABC @50 and writes 3 ABC Aug 55 calls @1.50. His maximum loss is . . .

I chose "unlimited" because of the short call position--what am I missing?

REPSONSE:

If the investor only wrote the three ABC Aug 55 calls, his risk would be unlimited, but this investor already bought the 300 shares he is obligated to sell and deliver for $55 a share. Therefore, he no longer worries about the stock rising; in fact, that would be his maximum gain. If the stock rises, he can make $5 per share plus the premium . . . maximum. His maximum loss is now pointing downward--he owns the stock. If it drops from $50 to zero, all he got to offset that was $1.50 per share. His maximum loss, then, is still $48.50 per share, times 300 shares.

Yikes.

That's why they say that covered calls provide "partial protection." The premium income is a nice way to "increase yield" or "increase overall return" on the stock, but it does very little to protect against a big drop. The best way to protect a long stock position, remember, is to buy a put. Having the right to sell your stock at a set price in case it drops is much better than having to sell your stock at a set price only if it goes up. I'm going to leave you with that thought--enjoy.

I saw a question like the one below on the software my firm gave me--I think it's an internal product somebody higher up put together. I don't think there's a right answer. Can you help?

Here is the qestion:

An investor purchases 300 shares ABC @50 and writes 3 ABC Aug 55 calls @1.50. His maximum loss is . . .

I chose "unlimited" because of the short call position--what am I missing?

REPSONSE:

If the investor only wrote the three ABC Aug 55 calls, his risk would be unlimited, but this investor already bought the 300 shares he is obligated to sell and deliver for $55 a share. Therefore, he no longer worries about the stock rising; in fact, that would be his maximum gain. If the stock rises, he can make $5 per share plus the premium . . . maximum. His maximum loss is now pointing downward--he owns the stock. If it drops from $50 to zero, all he got to offset that was $1.50 per share. His maximum loss, then, is still $48.50 per share, times 300 shares.

Yikes.

That's why they say that covered calls provide "partial protection." The premium income is a nice way to "increase yield" or "increase overall return" on the stock, but it does very little to protect against a big drop. The best way to protect a long stock position, remember, is to buy a put. Having the right to sell your stock at a set price in case it drops is much better than having to sell your stock at a set price only if it goes up. I'm going to leave you with that thought--enjoy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)